1920: The Age of Innocence, by Edith Wharton (USA)

1922: Ulysses, by James Joyce (Ireland)

1922: The Waste Land, by T.S. Eliot (USA)

1922: The Velveteen Rabbit, by Margery Williams (England)

1924: A Passage to India, by E.M. Forster (England)

1925: The Trial, by Franz Kafka (Germany)

1925: The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (USA)

1925: Mrs. Dalloway, by Virginia Woolf (England)

1926: Winnie-the-Pooh, by A.A. Milne (England)

1926: The Sun Also Rises, by Ernest Hemingway (USA)

1926: The Call of Cthulhu, by H.P. Lovecraft (USA)

1927: Elmer Gantry, by Sinclair Lewis (USA)

1927: To the Lighthouse, by Virginia Woolf (England)

1928: All Quiet on the Western Front, by Erich Maria Remarque (Germany)

1928: The Tower, by W.B. Yeats (Ireland)

1928: Orlando, by Virginia Woolf (England)

1929: The Sound and the Fury, by William Faulkner (USA)

1930: The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett (USA)

1930: As I Lay Dying, by William Faulkner (USA)

1931: The Good Earth, by Pearl S. Buck (USA)

1932: Brave New World, by Aldous Huxley (England)

1933: The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, by Gertrude Stein (USA)

1934: Mary Poppins, by P.L. Travers (England)

1934: Murder on the Orient Express, by Agatha Christie (England)

1934: Tropic of Cancer, by Henry Miller (USA)

1935: Little House on the Prairie, by Laura Ingalls Wilder (USA)

1936: At the Mountains of Madness, by H.P. Lovecraft (USA)

1936: Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell (USA)

1937: Out of Africa, by Karen Blixen (Denmark)

1937: Death on the Nile, by Agatha Christie (England)

1937: Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck (USA)

1937: The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien (England)

1937: Their Eyes Were Watching God, by Zora Neale Huston (USA)

1938: Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier (England)

1939: The Grapes of Wrath, by John Steinbeck (USA)

1939: The Day of the Locust, by Nathanael West (USA)

1939: Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats, by T.S. Eliot (England)

1939: The Big Sleep, by Raymond Chandler (USA)

1939: Madeline, by Ludwig Bemelmans (USA)

1940: For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway (USA)

1940: The Master and Margarita, by Mikhail Bulgakov (Russia)

1941: Make Way for Ducklings, by Robert McCloskey (USA)

1942: The Stranger, by Albert Camus (France)

1942: Runaway Bunny, by Maragaret Wise Brown (USA)

1944: The Razor’s Edge, by Somerset Maugham (England)

1945: Animal Farm, by George Orwell (England)

1945: Brideshead Revisited, by Evelyn Waugh (England)

1945: Stuart Little, by E.B. White (USA)

1945: Pippi Longstocking, by Astrid Lindgren (Sweden)

1947: The Diary of a Young Girl, by Anne Frank (the Netherlands)

1947: Goodnight Moon, by Maragaret Wise Brown (USA)

1948: The Cantos, by Ezra Pound (USA/Italy)

1948: Blueberries for Sal, by Robert McCloskey (USA)

1949: Nineteen Eighty-Four, by George Orwell (England)

1950: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, by C.S. Lewis (England)

1950: I, Robot, by Isaac Asimov (USA)

1950: The Martian Chronicles, by Ray Bradbury (USA)

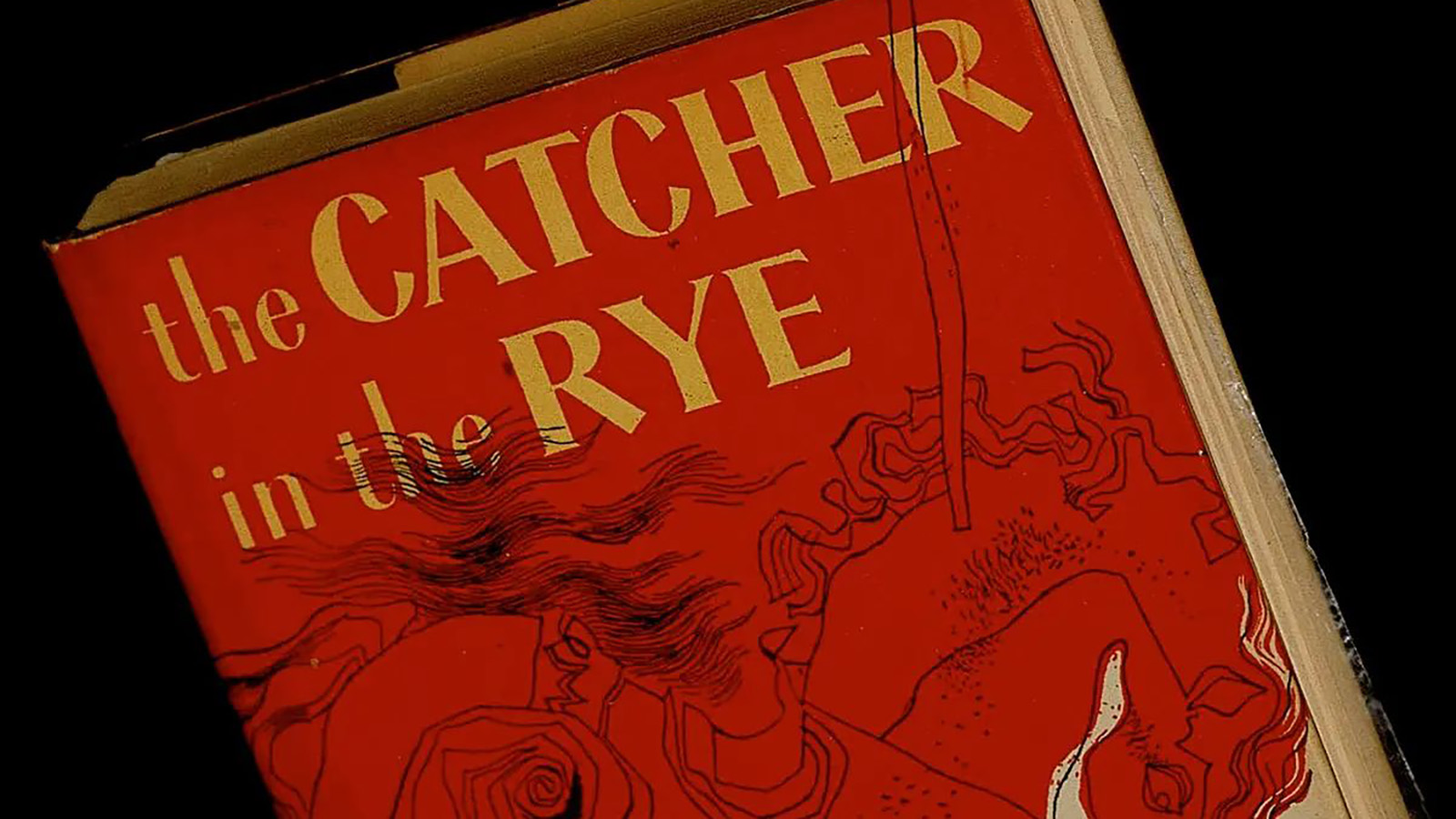

1951: The Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger (USA)

1951: The Illustrated Man, by Ray Bradbury (USA)

1952: The Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison (USA)

1952: Charlotte’s Web, by E.B. White (USA)

1952: The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway (USA)

1952: East of Eden, by John Steinbeck (USA)

1953: Casino Royale, by Ian Fleming (England)

1953: The Long Goodbye, by Raymond Chandler (USA)

1954: The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, by J.R.R. Tolkien (England)

1954: Lord of the Flies, by William Golding (England)

1954: Fahrenheit 451, by Ray Bradbury (USA)

1954: I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson (USA)

1955: Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov (USA)

1955: Beezus and Ramona, by Beverly Cleary (USA)

1955: Harold and the Purple Crayon, by Crockett Johnson (USA)

1955: The Last Temptation of Christ, by Nikos Kazantzakis (USA)

1955: Eloise, by Kay Thompson (USA)

1956: Howl, by Allen Ginsberg (USA)

1957: The Cat in the Hat, by Theodor Seuss Geisel (USA)

1957: On the Road, by Jack Kerouac (Canada)

1957: Atlas Shrugged, by Ayn Rand (USA)

1957: The Guns of Navarone, by Alistair MacLean (England)

1957: Franny and Zooey, by J.D. Salinger (USA)

1958: The Lottery, by Shirley Jackson (USA)

1958: Breakfast at Tiffany’s, by Truman Capote (USA)

1958: Things Fall Apart, by Chinua Achebe (Nigeria)

1958: A Bear Called Paddington, by Michael Bond (England)

1959: Naked Lunch, by William S. Burroughs (USA)

1959: The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson (USA)

1959: Starship Troopers, by Robert A. Heinlein (USA)

![Angel Blue and Eric Owens in Porgy and Bess, photo by Ken Howard. [Metropolitan Opera]](/globalassets/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/artsedge/media/understanding-opera/porgy-and-bess-2-169.jpg?width=768&quality=70)