1865: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Caroll (England)

1865: From the Earth to the Moon, by Jules Verne (France)

1866: Crime and Punishment, by Fyodor Dostoevsky (Russia)

1868: Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott (USA)

1869: War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy (Russia)

1870: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, by Jules Verne (France)

1872: Around the World in Eighty Days, by Jules Verne (France)

1873: A Season in Hell, by Arthur Rimbaud (France)

1874: Far From the Maddening Crowd, by Thomas Hardy (England)

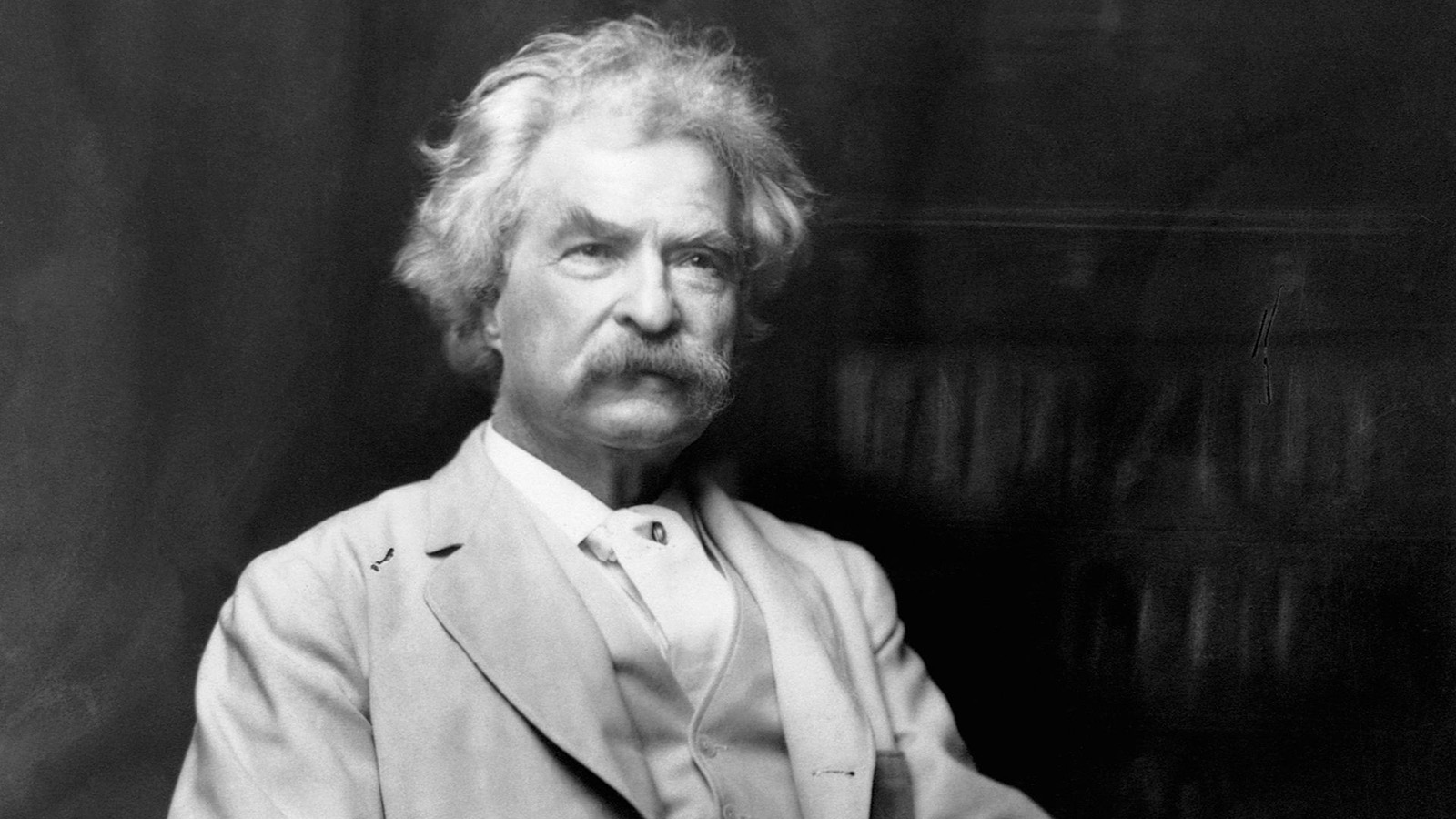

1876: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain (USA)

1878: Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy (Russia)

1879: The Red Room, by August Strindberg (Sweden)

1880: Boule de Suif, by Guy de Maupassant (France)

1880: The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky (Russia)

1883: Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson (Scotland)

1884: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain (USA)

1886: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson (Scotland)

1890: The Picture of Dorian Grey, by Oscar Wilde (Ireland)

1890: An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, by Ambrose Bierce (USA)

1891: Tess of the d’Urbervilles, by Thomas Hardy (England)

1891: Billy Budd, by Herman Melville (USA)

1894: The Jungle Book, by Rudyard Kipling (England)

1895: The Time Machine, by H.G. Wells (England)

1895: The Red Badge of Courage, by Stephen Crane (USA)

1896: The Island of Doctor Moreau, by H.G. Wells (England)

1897: Dracula, by Bram Stoker (Ireland)

1897: The Invisible Man, by H.G. Wells (England)

1898: The Turn of the Screw, by Henry James (USA)

1898: The War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells (England)

1900: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, by L. Frank Baum (USA)

1901: The Tale of Peter Rabbit, by Beatrix Potter (England)

1902: Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad (USA)

1902: The Hound of the Baskervilles, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Scotland)

1903: The Call of the Wild, by Jack London (USA)

1904: Peter Pan, written by J.M. Barrie (Scotland)

1904: Nostromo, by Joseph Conrad (USA)

1906: The Jungle, by Upton Sinclar (USA)

1907: The Secret Agent, by Joseph Conrad (USA)

1908: Anne of Green Gables, by Lucy Maud Montgomery (Canada)

1908: The Wind in the Willows, by Kenneth Grahame (England)

1908: A Room with a View, by E.M. Forster (England)

1910: Howards End, by E.M. Forster (England)

1911: The Secret Garden, by Frances Hodgson Burnett (England)

1912: Tarzan of the Apes, by Edgar Rice Burroughs (USA)

1913: Remembrance of Things Past, by Marcel Proust (France)

1915: Of Human Bondage, by Somerset Maugham (England)

1915: Rashōmon, by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (Japan)

1915: The Metamorphosis, by Franz Kafka (Germany)

1916: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, by James Joyce (Ireland)

1916: Women in Love, by D.H. Lawrence (England)

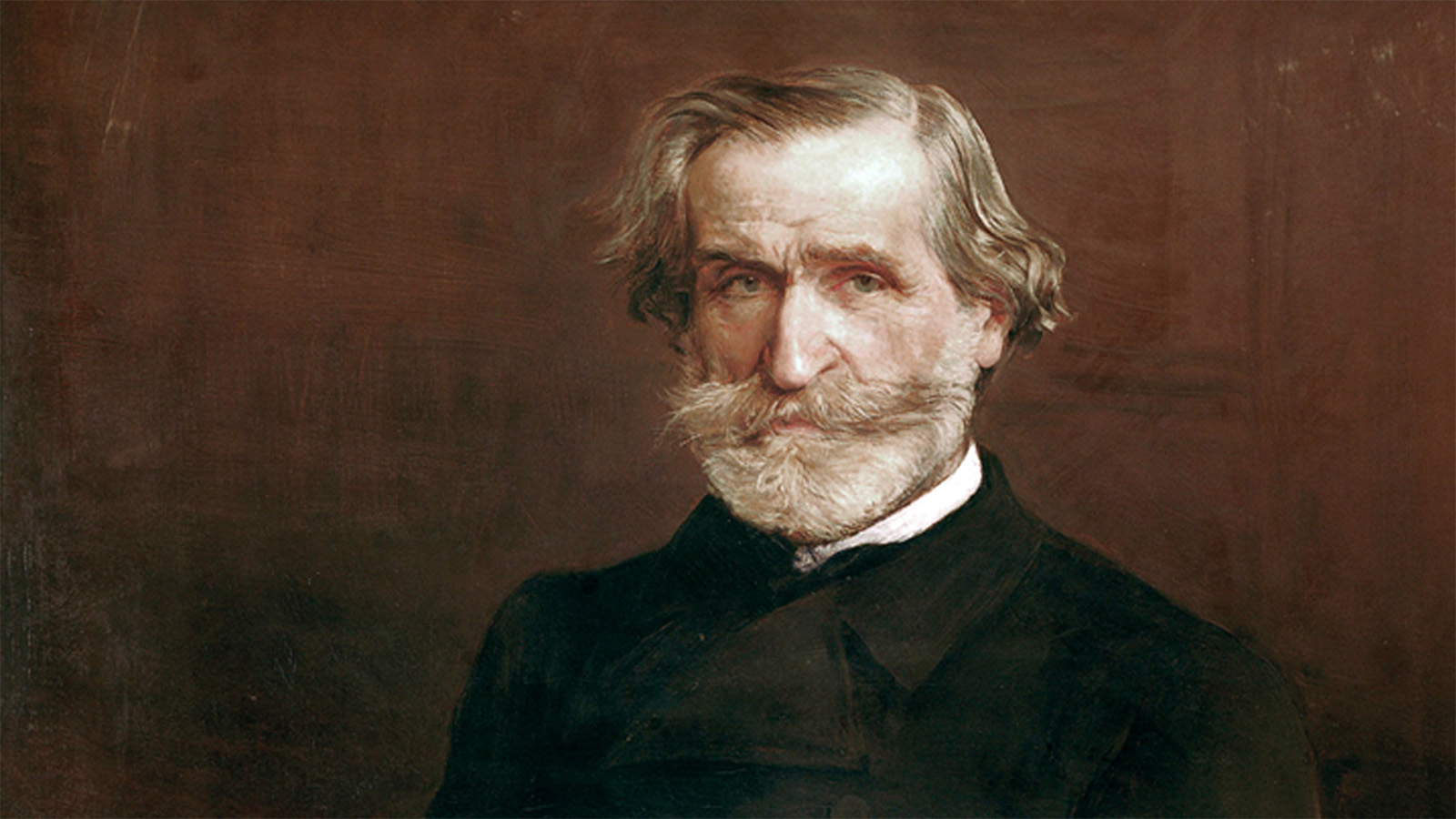

Giuseppi Verdi

Giuseppi Verdi